Welcome to the third issue of Higher Ed Conversations in Black.

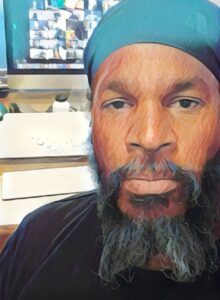

The edition is framed by Steve Desir, Program Coordinator for the Inclusive Graduate Education Network (IGEN) Research Hub and doctoral candidate in the Educational Leadership program at USC Rossier School of Education.

Black History Month — A Moment for Pause and Action

February, 2022

This month, colleges and universities across the United States celebrated Black History Month. Campuses hosted celebrations, sponsored colloquia, and adorned their campuses with banners and exhibits that celebrated those faculty and students who have opened the doors of opportunity for others by being “the first.” I must admit, I look forward to February each year because, for 28 straight days, I am reminded that #BlackExcellence surrounds me and has contributed significantly to the tapestry of American higher education.

As we gathered to celebrate what was once Negro History Week 96 years later, I am reminded of what Carter G. Woodson intended when he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) in 1925, which coordinated and celebrated the first Negro History Week in 1926. Dr. Woodson hoped that Black History Month would be a vehicle for advancing the study and teaching of Black History.

Ninety-six years later, as a Black student, researcher and former administrator, Black History Month is a time for reflection, inspiration and hope. It is a time when I am steeped in works of art that celebrate the totality of the Black experience. It is also a time when I embrace the scholarship of Black researchers who provide full histories that recognize the substantial challenges that my ancestors had to overcome. Lastly, Black History Month is an opportunity for me to challenge my colleagues in higher education to recognize and support the contributions being made to Black history by faculty, staff and students in our classrooms, laboratories and university offices.

In 2022, it is my hope that university presidents, academic deans and administrators will honor the life and legacy of Dr. Woodson and the many Black firsts that have transformed their campuses by broadening their commitments to policy and practice that will improve the material conditions of the Black faculty, staff and students who are members of their community today.

For our third issue of Higher Ed Conversations in Black, we asked Black scholars and thought leaders in the higher education community to answer the following questions: What meaning does Black History month hold for you this month? What should higher education institutions do in this pivotal moment to center and honor Black people and their contributions to reimagining our institutions?

This month especially, I want to close with a personal note to the Black faculty, staff and students who might be reading Higher Ed Conversations in Black. I want you to know that I see you. I want to thank you for all of the invisible labor you do mentoring and supporting others. I know that I am the person I am today because of Black faculty, staff and students who have nurtured and supported me. I recognize that I stand on the shoulders of giants who climbed through windows to open doors of opportunity for me, and for that, I am eternally grateful.

– Steve Desir

Contributors

James Bridgeforth

Ph.D. Candidate, Former K-12 Teacher

Dr. Alan Green

Professor of Clinical Education at USC, Spirit Elevator

Dr. Royel Johnson

Scholar, Professor, Interdisciplinarian

Dr. Amelia Parnell

VP for Research & Policy at NASPA, Optimist, Connector and Friend

Patti Colston

Chief Consultant to the California Legislative Black Caucus (CLBC) @ the State Capitol, Associate Adjunct Professor, Advocate for Digital Innovation in College Access for Low-income Students

click contributor names for bios

What meaning does Black History month hold for you this month? What should higher education institutions do in this pivotal moment to center and honor Black people and their contributions to reimagining our institutions?

James Bridgeforth: Admittedly, answering this question has been difficult for me as I continue to reflect on the many ways that anti-Blackness remains an ever-present reality in our lives. Before I begin to offer suggestions for higher education institutions to meaningfully center and honor Black people, I realize that I’m left with more questions than answers. For example, I want to ask where is the evidence that many higher education institutions have historically chosen to do so? And where is the evidence that many current higher education leaders have the willingness and capacity to do so? This is not to say that these efforts are impossible, but more to question what will it take for the possibility to become the reality? Black people are often asked to provide suggestions and recommendations on how to transform historically white-serving institutions. Yet how many times are those suggestions and recommendations actually implemented in the ways that they were suggested? That is, without adaptation to prioritize the whims and needs of the university? I choose to remain hopeful that the needs, hopes and dreams of Black people will one day be prioritized in higher education institutions, particularly as many now espouse antiracist and equity-focused visions. But until that day comes, I am left with the thoughts of James Baldwin: “I can’t believe what you say, the song goes, because I see what you do.”

James Bridgeforth: Admittedly, answering this question has been difficult for me as I continue to reflect on the many ways that anti-Blackness remains an ever-present reality in our lives. Before I begin to offer suggestions for higher education institutions to meaningfully center and honor Black people, I realize that I’m left with more questions than answers. For example, I want to ask where is the evidence that many higher education institutions have historically chosen to do so? And where is the evidence that many current higher education leaders have the willingness and capacity to do so? This is not to say that these efforts are impossible, but more to question what will it take for the possibility to become the reality? Black people are often asked to provide suggestions and recommendations on how to transform historically white-serving institutions. Yet how many times are those suggestions and recommendations actually implemented in the ways that they were suggested? That is, without adaptation to prioritize the whims and needs of the university? I choose to remain hopeful that the needs, hopes and dreams of Black people will one day be prioritized in higher education institutions, particularly as many now espouse antiracist and equity-focused visions. But until that day comes, I am left with the thoughts of James Baldwin: “I can’t believe what you say, the song goes, because I see what you do.”

Dr. Alan Green: Black History Month has always been a sweet but bitter time of the year for me. On the one hand, I am always proud to pay homage to the mighty examples of Black and African excellence throughout history and in contemporary times. Yet, on the other hand, I struggle with the need to designate and set aside a time to once again attempt to verify, justify and signify our humanity. Like most, I have come to accept the good and bad with this. Particularly as a parent and an educator, I do look forward to discussing Black and African heritage with young people and engaging with them about the reasons for celebration. This year, given all of the significant challenges and opportunities before us, I have felt even more committed than ever to challenge higher education as a field to be better. This of course brings me back to the bitterness of it all. I guess this comes with the dual consciousness W.E.B. Du Bois so eloquently taught us about.

Dr. Royel Johnson: In one of his foundational texts, “Faces of the Bottom of the Well,” critical race theory progenitor and lauded scholar Derrick Bell introduces the concept of “racial symbols.” Racial symbols are those things (e.g., public statements, legal decisions, statues, appointment of leaders) that hold mostly symbolic or abstract value. In other words, they do very little to improve the material conditions and realities of racially- and ethnically-minoritized people. Bell’s concern was that what is often touted as watershed victories in our nation’s quest for a more perfect union, such as the Brown v. Board of Education decision, appointment of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, and the establishment of a holiday to honor the late Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., are merely symbolic gestures. Black History Month, despite its well-intentioned purpose, is a racial symbol. Institutions across industries celebrate the considerable contributions of Black people during the month of February each year while simultaneously conspiring in our marginalization through oppressive policies, practices and organizational cultures. Higher education institutions are no different. We can honor the legacy and contributions of Black people by taking seriously and addressing the ways in which anti-Black violence and white supremacy coalesce in shaping the experiences of Black faculty, staff and students on campus.

Dr. Amelia Parnell: I always feel proud of the Black people who paved the way for me, but I am especially thankful for their contributions during Black History Month. From the inventors of the products I use regularly to the activists who fought and died for my freedom, Black History Month provides a daily reminder for me to celebrate these trailblazers and their achievements in overcoming seemingly insurmountable adversity. With regard to the field of higher education, this is a good time for the industry to seek guidance from Black leaders, practitioners, researchers, scholars and students. As the field of higher education becomes a more responsive, influential and transformational enterprise, amplifying the voices of Black leaders and embracing their wisdom and experience will benefit the entire field in the years ahead. By intentionally including Black perspectives in our redesign of critical policies and practices, we can help ensure that every student has a valuable college experience. This is the legacy of excellence I am happy to celebrate and which inspires me to work hard to open doors for the generations who will follow me.

Patti Colston: Carrying on the legacy of family as a third generation African-American female college graduate, this year hit a little different for me. Now is the perfect time to have truthful conversations on race in safe spaces: college and university campuses are ideal spaces to facilitate, rather than avoid these important discussions.

I’m celebrating Black History Month this year with a whole new outlook on life. After a DNA test, genealogy research, and scouring U.S. Census records, I learned that my ancestors worked on the Underground Railroad with Harriet Tubman. This discovery explains a lot about who I am, including my “speak truth to power” personality. And perhaps even why I selected to portray the legendary Tubman in an elementary school play about her.

In 1965, when I was a child growing up in South Los Angeles, the Watts riots erupted about 10 miles east of my home. My school, Manhattan Place, was closed down and National Guardsmen armed with rifles and parked in tanks, blocked off my street so my mom and I couldn’t go to the grocery store.

After the riots ended and we resumed classes, the complexion of my school had changed. My teachers were Black now. Wearing afros and dashakis. They had us watch and recite from the classic documentary, “I am Somebody.” We studied Black history every day of the year — not just for one month. My educators, all recent CSU Or UC graduates, drove Camaros and Firebirds. They inspired me to exist comfortably in my Blackness, unapologetically, and I learned early to protect my right to celebrate my authenticity. We sang Donnie Hathaway’s “Young, Gifted and Black” and James Brown’s “Say it Loud.” We believed every word.

In 1992, I was a television news producer and writer, living and working in Sacramento. After earning a Master of Science in Mass Communications, I reported on the trial verdict that led to the Rodney King riots. I was the only African American working in the newsroom at the time and all of other staff kept staring at me. I, on the other hand, was staring at the bank of TV monitors on the wall as they showed a close-up of Bertha’s Soul Food restaurant, located just steps from where I grew up, as it went up in flames and burned to the ground.

In 2020, as a teleworking state worker, I was assigned to assist with the COVID-19 response. From the solitude of my home office, I watched as the Black Lives Matter movement unfolded before my eyes on social media. The cries for social and racial justice were finally being heard, amplified around the nation, and across the world.

Today, as an Assistant Professor for a California community college, and as a Senior Consultant for the California Legislative Black Caucus, my career is dedicated to aligning our history with the future. As a direct descendant of those who lived and died guiding families to freedom, I believe public service and teaching are in my blood. Let’s bring more prosperity to African Americans in California through higher education policy, practice and the political process. That’s the route for today’s Underground Railroad.

HIGHER ED CONVERSATIONS IN BLACK

Issue 03 | Edited by Jordan Harper, Zoë Corwin and Adrianna Kezar | Created by Jordan Harper