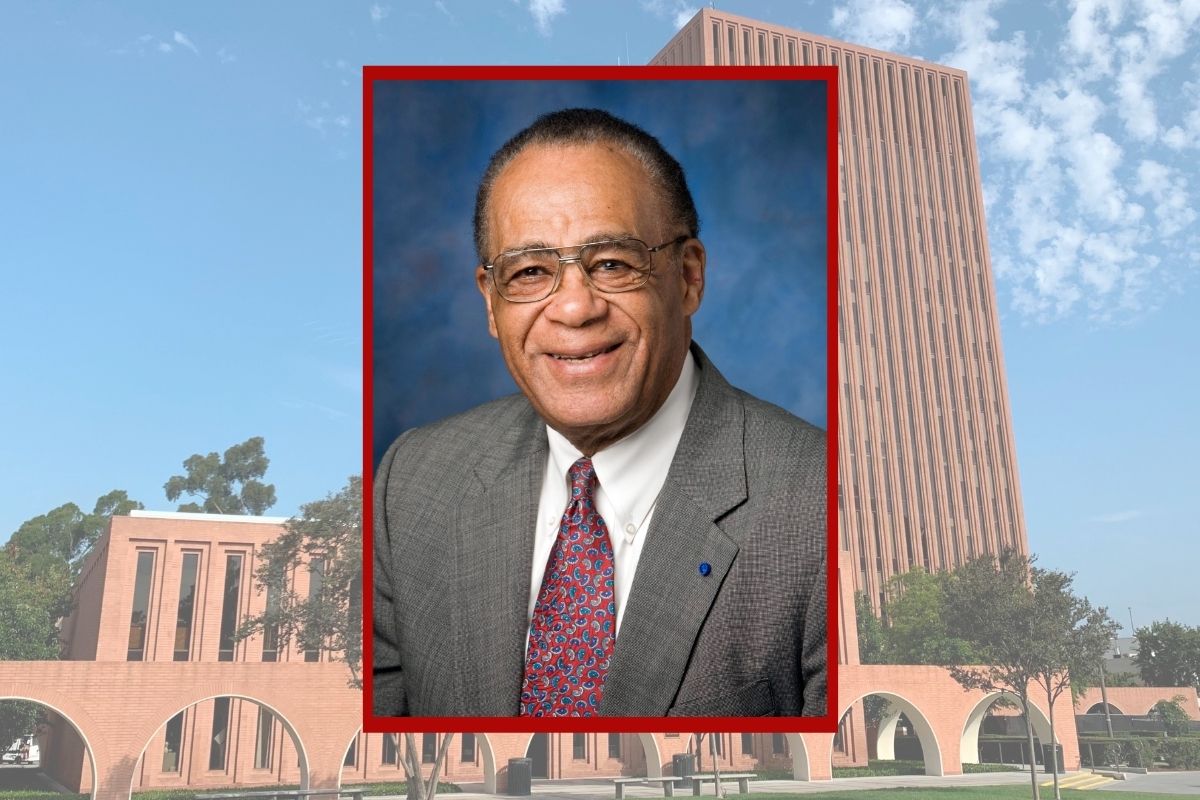

John Brooks Slaughter: Engineering a Better Education

The Pullias Center’s John Brooks Slaughter reflects on his unique role at the intersection of education and engineering.

There have been many occasions when I have been asked, “What does a Professor of Education and Engineering do?” Over time I have developed an answer that on the surface may seem glib or flippant. I say, my job is to teach education students something about engineering and engineering students something about education. But because of the overwhelming events of the past year, I have decided that the explanation is not as offhand or dismissive as it may appear but more substantive and germane than even I had thought.

2020 was a year in which everyone was impacted by the novel pandemic, Covid-19, and those of us in this country experienced the calls for racial justice and the end to police brutality in the wake of the tragic and senseless murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Eric Garner, among others, especially African Americans. It was also a time when we saw enormous political divisiveness and the emergence of white supremacists who had been mostly undercover until they were emboldened and encouraged to make their presence known.

As a result of the pandemic, for example, students at all levels, from elementary school to graduate school were forced to study and take classes online rather than in person in a classroom. They were required to have a computer and its accessory equipment, broadband internet service capability and the software and hardware skills to facilitate their educational pursuits. Students who did not possess or have access to the requisite technological tools and/or lacked the necessary skills to effectively use digital technology found it difficult if not impossible to pursue their education. The pre-pandemic educational inequities that existed for many poor and marginalized students were exacerbated by the requirements imposed upon them by the onset and existence of the coronavirus. The arrival of Covid-19 was a heads-up signal for the need for all students to become technologically literate in a world where technology is expanding exponentially and changing the way we learn, communicate and work. Students whose interests or majors are in the fields of education and any of the liberal arts, humanities, and social sciences will need an exposure to and some understanding of the principles and concepts of the physical and natural sciences, technology, engineering, and mathematics, the STEM disciplines, if they are to be productive and engaged citizens in society.

As an engineer, I have the opinion that too many engineering students graduate from engineering programs in which they have been trained rather than educated. The core curriculum that many engineering students study is void of the liberal arts and social sciences courses that they need to be successful practitioners in today’s environment of global competitiveness, rapid demographic changes, and societal disruptions. I would argue that exposure to those types of courses is required if they are to acquire the ability to be effective in a world that is becoming increasingly complex, multicultural, and interdependent. The failure to become familiar with these fields of study means that their effectiveness after graduation will be severely limited. The global challenges facing the engineering profession, such as climate change, renewable energy, cyberspace security, and personalized learning, for example, cannot be solved by math and science alone. They will require an appreciation of and an engagement with the liberal arts, humanities, and the social sciences to achieve workable and long-lasting solutions. Engineers must recognize that not only must they satisfy the physical constraints and technical requirements of their designs and deliverables, but they must also take into account, among other things, the economic constraints, the needs, and aspirations of the intended users of the artifacts that are produced, the potential unintended impacts of their solutions, and, often, the political environment in which they are operating. It is needless to say that a STEM education alone will not be sufficient. If that is all they receive, to paraphrase Benjamin Spock, they will enter their profession “literal-minded, uninformed about the world, and insensitive.”

It is my opinion that a STEM education should be much more than the study of the principles and applications of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. A STEM education, I believe, should also be about learning critical thinking, recognizing patterns, identifying, addressing, and solving problems, learning to question what appears to be the obvious, developing an understanding of both the natural and physical worlds, engaging with life.

To overcome its limitations, it has been proposed by many to change STEM education to STEAM education where the “A” is intended to imply the Arts. I like to think of the added “A” as any academic discipline. My colleague, Professor Anthony Maddox, the director of the Rossier Center for Engineering in Education, and I prefer to envision a STEEM education where the additional “E” connotes every academic discipline. We believe fervently that every field of learning can be enhanced by the appropriate introduction of some STEM tenets and practices.

I want to believe that a Professor of Education and Engineering should be someone who studies and teaches what Dr. Eswaran Subrahmanian of Carnegie Mellon University described in his book, Designing: The Verb, “…. a field of study that embraces disciplinary diversity, drawing from science, engineering and technology, social science, and art. An arena of practice where people are the focus, where different perspectives can come together and shape the world.”

The next time someone asks me, “What does a Professor of Education and Engineering do?”, that is the answer I will give.