Pullias Center 25th Anniversary Reflections: William G. Tierney

William G. Tierney, University Professor Emeritus and the Founding Director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California, shares his reflections on the center as we celebrate our 25th Anniversary. This is the first in a series of such reflections from key figures in the center’s past and present that will be shared throughout 2020.

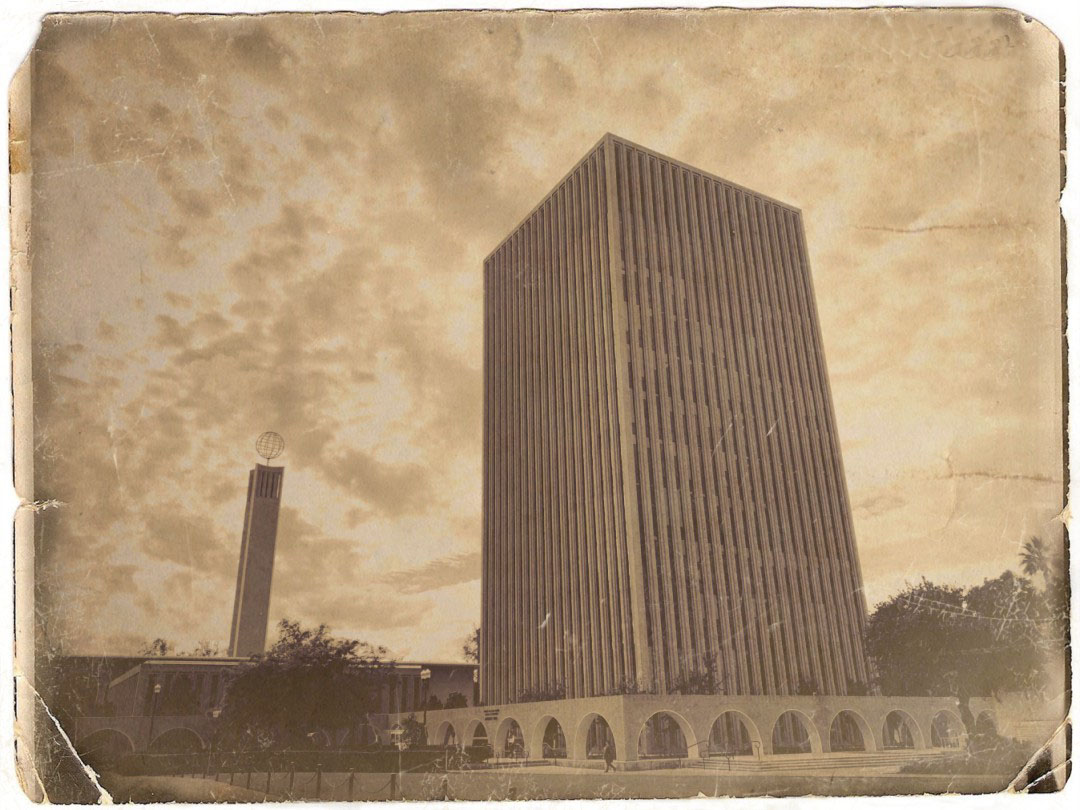

I came to USC from Penn State in 1994. At Penn State I was in one of the most prestigious postsecondary centers in the country – the “Center for the Study of Higher Education.” A center devoted specifically to the study of a topic enables intellectual cohesion in the way a department or division does not. Departments and divisions certainly can be useful building blocks for academic strengths, but I wanted to focus on the study of higher education. For the first year, in 1995, I was the Center for Higher Education at USC. I had a secretary, a grad assistant, and an empty set of offices on the 7th floor in Waite Phillips Hall. We then hired Estela Bensimon and additional faculty and staff followed.

There were two critical differences between the Pullias Center and other centers of higher education. First, most centers had a generic mission – scholars studied various facets of higher education in their country. Second, most centers were located at public universities and had core funding either from their College or the central administration. The first was intentional on my part; the ramifications of the second I learned about the minute I arrived.

I wanted a center with a dual focus – governance in higher education, and issues of equity. The utility of a mission is not simply stating what one does; it also helps us define what we do not do. I didn’t want the Center to be a grab-bag of topics that we simply studied, wrote a paper, and then went on to another topic. Throughout our history we have largely focused on issues of governance and leadership, and equity. As times have changed, so has our approach. When I arrived at USC I never would have thought of studying games as a way to improve the chances of low-income youth to attend college. Similarly, the phrase “gig economy” did not exist in 1994, and studying part-time faculty would have been relatively unimportant 25 years ago, whereas it is critical today.

A private university that functioned by way of revenue-centered management also meant that I had to be more aware of how to generate revenue. True, other centers sought grants, but a quarter of a century ago we were more aggressive than any other center in the country in searching out funding from a variety of sources – not simply the federal government, but also states, foundations, corporations, and most importantly, donors. We were the first, and to date we are the only, endowed center for higher education in the country. When Earl Pullias’s son Calvin passed away and gave the bulk of his estate to endow the Pullias Center we knew that our center would live and thrive well beyond my participation.

We also had to develop a plan for hiring faculty. Hiring new faculty is always an opportunity, but is also fraught with conflict. Some departments have done extremely well by hiring individuals who were more similar than different. The “Chicago School” of economics at the University of Chicago is perhaps the best example of a group of first-rate intellectuals who largely adhered to the same intellectual agenda. Methodology also can be the driving force for hiring decision when quantitative researchers, for example, only want to hire others who are similarly trained. One risk of hiring the mirror image of those who are already there is that departments end up with everyone looking alike – largely white men, and the intellectual agenda is more similar than different.

I wanted us to hire individuals who were diverse rather than similar. The result, 25 years later, is that we have quantitative and qualitative researchers, men and women, Anglo, African American, Asian American, and Latinx researchers, and individuals who approach topics of governance and equity from many different intellectual perspectives. We also have an international focus that sets us apart from most of our counterparts.

One final difference between the Pullias Center and other centers when we began is that we were explicitly concerned with outreach. Most centers do what academics do best – write research papers that get published in journals. I wanted us to increase our presence in three ways. First, a few centers were concerned about public policy and I wanted to continue that tradition, but I also wanted to reach out to various communities that ordinarily didn’t receive much research-informed work about our colleges and universities. I believe we were the first center of higher education that put out a quarterly newsletter that went to thousands of individuals. Second, over the years we have written, arguably, more op-eds, opinion pieces, and public policy documents than any other higher education center at a university. We also have extended our reach by studying abroad. The faculty have had research fellowships in Asia, Latin America, Europe and Canada.

And third, I wanted us to ‘walk our talk.’ We have had mentoring programs in the schools where we use the research we’ve written to help improve access for low-income youth. We have had a summer writing program to improve the college readiness of college-bound youth. Doing research in the Pullias Center has meant being involved not simply in cutting-edge research, but also putting what we know into practice.

I can’t say that every attempt we made was successful. We have played a ‘razzle-dazzle’ style of work, rather than the staid, toned-down approach of many of our colleagues. When we have aggressively approached funders, or policy experts about an idea we have had, we have not always been successful – but we are batting well above average. Because we have been aggressive and certainly made an impact, I have every confidence that the next quarter century will be as exciting as the past has been. I do not expect the Pullias Center to rest on its successes and look forward to seeing the sorts of changes that enable us to continue our trajectory as a premier research center.